Read, watch or listen to anything – absolutely anything – by Stan Tatkin, a neurobiologist who peers into the human brain and nervous system to explain why so many of us screw up when it comes to love. Then, he provides specific instructions on how to avoid those pitfalls and instead strengthen our pairings.

What a relief to hear common sense that cancels out contemporary claptrap. Tatkin takes issue with some of today’s false memes:

- no one can make us feel a certain way unless we let them

- we need to love ourselves before we can love another

- we need to take care of ourselves first

Not true, he says. Relying on recent discoveries in neurology, Tatkin dispatches this nonsense to the garbage heap where many of us always sensed it belongs. Instead, he points out:

- Our first experience of love is one-way, and it comes from our primary caregivers (usually mother). We learn how to love ourselves, or not, based on the love we received from them.

- We are set up for pair bonding based on the first pair, that of (usually) mother and child. For the rest of our lives we will look to replicate a similarly deep bond with one other person.

- How we bonded with our primary caregivers will set the tone for our future relationships. This is known as attachment theory.

- Our brain structures are more attuned to war than to love, and this is one of the main hindrances to successful relationships. Luckily, Tatkin shows us workarounds.

For example, what’s known as our reptilian brain – let’s call it that for simplicity’s sake — is very attuned to threats. (The old reptiles were ready for the four F’s: Fight, flight, feed and f… well, you know.) When a partner disses us, snaps, or acts in a passive-aggressive way, our reptilian brain registers this as a threat. In fact, the human brain is marked by the beloved’s nasty words way more than it is by his or her sweet nothings.

Tatkin divides love styles into the three categories of anchors, waves and islands, based on the three main attachment styles known as securely attached, insecurely avoidant and insecurely ambivalent. People can switch between the different categories, he says, but decades of research have established that the qualities of our earliest relationships with our primary caregivers set us on a course for life. Many people possess traits from different groups, but even card-carrying waves or islands are capable of rewiring to a certain extent. He says people who didn’t have great childhoods “are at greater risk for forming insecure adult relationships. I’m not saying you can’t have wonderful, satisfying and enduring relationships. But you may have to work harder at it.”

[His quiz pegged me as belonging solidly in both wave and island categories. So THAT explains it….]

He stresses that waves and islands in relationships need to recognize that instead of fixing each other, we will adopt each other. In one book, he writes, “You will take on each other’s injuries, past and current, as well as each other’s family issues and relationship issues. You will have a lot of heavy lifting to do.”

As consolation, though, the personalities of two people do not make or break a relationship. What matters is the degree of willingness on the part of both partners to create and sustain a secure, functioning relationship. And islands or waves are less inclined to behave in ways that consistent with secure functioning.

Islands tend not to be very emotionally expressive, physically affectionate, interpersonally collaborative or outwardly needy. But inside the island is often a fragile self, unsure how to deal with stressful internal thoughts, feelings and experiences. In terms of attachment security, it is difficult for them to bond with others, and close relationships remain fuzzy and inexplicable to the island mind. They don’t realize that their perceived ‘independence’ is just an adaptation to neglect in prior years and childhood. Scarlett O’Hara and Don Draper are prototypical islands.

Another piece of advice is that people should act the same in public as they do in private. In other words, the face we present to the outside world should be the same we enact in private.

[I hung my head. To the outside world I appear calm and tolerant, and 99% of the time that is how I conduct myself. But in love and family relationships, I have descended into impatience, anger and a tendency to nag.]

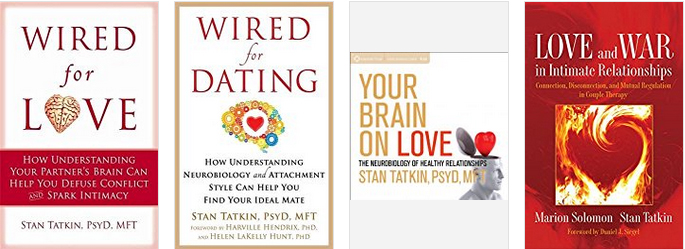

The book may spark a few quibbles. Tatkin advises “Sherlocking” about your potential partner and his or her family background, but he doesn’t really explain how to go about it. For example, in Wired for Dating, he advises teasing out your prospect’s anchor, wave or island status, but then doesn’t provide adequate instructions.

[Blind date scenario: “Pleased to meet you. After we order our drinks, would you confirm that your mother thrust you into the role of confidant because your father was an emotionally unavailable alcoholic/cheater/workaholic and is this why you’re thrice-divorced, unable to achieve true emotional intimacy? Oh, and by the way, are you willing to explore this in couples counseling?”]

Also, he suggests that you let your friends and family “vet” your prospective partner. The problem arises when friends and family are dysfunctional themselves. For example, two dear friends objected to a man whom I loved deeply because in their opinion his socio-economic status was too low. On the other side, his family was marked by generations of alcoholism, dysfunction and unhappiness, and his relatives objected to me for reasons informed by that family history. If you’re going to let friends and family vet your picks, make sure it’s not a case of the blind leading the blind.

Lastly, it may be nit-picking, but I feel compelled to mention it. Tatkin characterizes “islands” as snappy dressers because of a tendency to perfectionism. That may hold true in some professions, but the absolutely most deserted, solitary, isolated and lonely island I ever loved had a fashion sense from an uninhabited Pacific atoll. On a bearded and tattooed Brooklynite his Green Hulk T-shirt would have been a retro fashion statement, but on a senior citizen wearing tube socks and old sneakers, with calf muscles atrophied from lack of exercise poking out from army camouflage shorts, it was blissful unawareness. But this guy was a workaholic, a giveaway clue to his island working-class hero upbringing that valued jobs and money over people and relationships.

Wired for Love’s introduction, written by Harville Hendrix, puts into a much larger context the issues around pair-bonding. “The best thing a society can do for itself is to promote and support healthy couples, and the best thing partners can do for themselves, for their children, and for society is to have a healthy relationship…. This radical position – that by transforming couplehood we transform every social structure – has been in the making only in the last twenty-five years.”

This may be why Tatkin’s books rocked my world. I’m devouring every book I can get my hands on about couples and attend 12-step relationship programs in the hopes of making sense of a relationship that devolved into one-upsmanship, bullying and vindictiveness. Up until now, I ran from therapy for decades following an episode in the 1990s when I sought relationship help from psychiatrists whose solution was anti-depressants instead of inquiring how I felt. They also missed, as I did at the time, the rampant drug addiction in my family and my partner. And the few non-prescribing therapists I saw never spoke to me in ways that sparked the instantaneous and profound recognition that I felt upon hearing the opening words of Stan Tatkin’s CD set Your Brain on Love.

Reviews of the individual books and CDs to follow.

Recent Comments